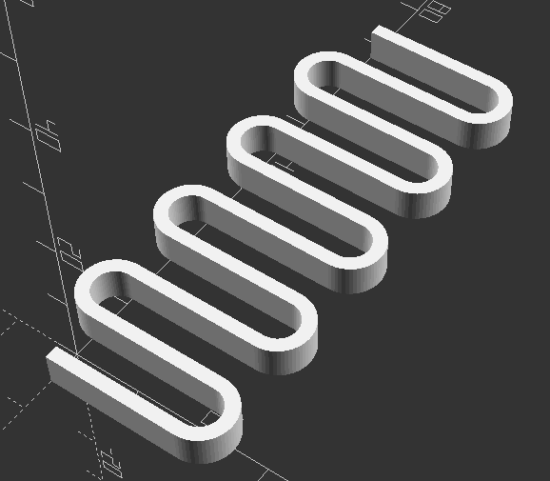

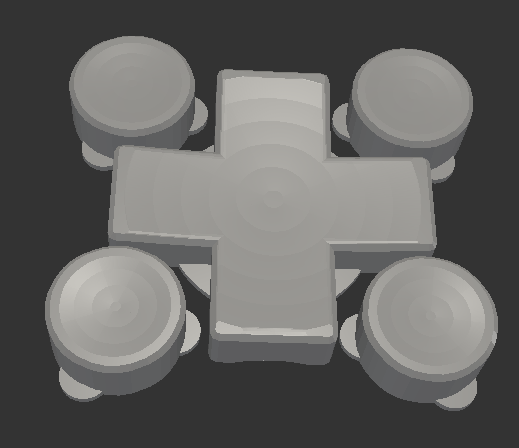

This week’s topic related to @deshipu’s directional keypad designs. The directional pad is clearly the most complicated part of the design. The four buttons are basically just cylinders that can be created in several different ways.

Brian published his designs to Github.

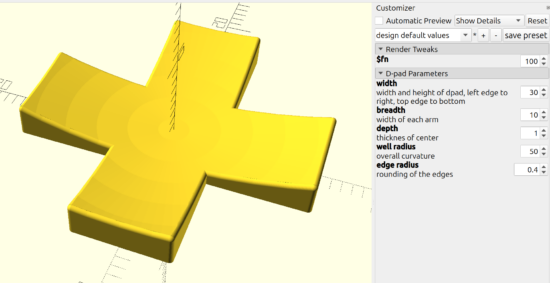

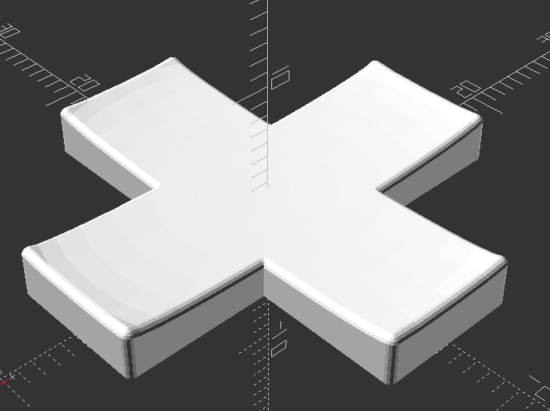

After staring at the design a little longer, I changed from my original design idea to creating a 2D cross, extruding that, subtracting out the curved area described by a sphere (a homebrew hack I’ll describe below), using the minkowski function to surround the entire surface with a small sphere to give it a rounded look, then cutting the bottom off to ensure it is flat. I didn’t include a flat cylinder as in the original design above, but that’s a trivial addition. The downside? This is a 5 minute render on my machine, largely due to the minkowski function.

// Settings

fn = pow(2,5);

// Measurements

pad = [10,30,1,3];

corner = 1;

dpad();

module dpad()

{

difference()

{

minkowski()

{

difference()

{

linear_extrude(height=pad[3], center=false)

offset(r=-corner/2, $fn=fn)

for (i=[0:1])

rotate([0,0,90*i])

square([pad[0],pad[1]], center=true);

translate([0,0,pad[3]])

scale([pad[1]*1.03,pad[1]*1.03,pad[3]-pad[2]])

sphere(r=0.5, $fn=fn);

}

sphere(r=corner/2, $fn=pow(2,4));

}

mirror([0,0,1])

cylinder(r=pad[1], h=pad[1], center=false);

}

}

Renders to:

Hacks:

- You’ll notice I use “offset” to reduce the size of the directional pad, because I knew I was going to round it all with the minkowski function in a few lines.

- The directional pad is actually just a rectangle, run through a for loop once to rotated it by 90 degrees, before being extruded to the specified height.

- The last two lines of code are used to create a large cylinder, larger than what I knew the pad would be, then mirrored in the Z axis to cut everything below the XY plane.

- As in prior designs, I pre-define “fn” to be a “pow(2,5)” so that I can use a low exponent to iterate designs quickly, then crank it up for a detailed design.

- The hack I use the most often here, and the one I’m the most proud of, is where I make a sphere like “sphere(r=0.5)” and then scale it by whatever I need. Since the sphere has a diameter of “0.5” mm, the actual sphere is 1mm in diameter – so when I scale it in the XY by 30 and in the Z by 2 (since the edges of the keypad are 3mm tall and the center is 1mm tall), the diameter is now 30mm and the height is 2mm. This little trick, of being able to scale a sphere to the exact size I need has come in handy countless times.

I’m not the best programmer, not the best at OpenSCAD, but I’m kinda happy that I was able to build this in about 31 lines of code. :)

#OpenSCADClub