Table Of Contents

1. Focus + Practice + Time = New Skills

2. Building a DIY Travel Ukulele

1. Existing Tutorials, Resources, Examples

1. Background

About two years ago I received a ukulele for Father’s Day and started playing it. It’s an instrument I’ve always been interested in, but nothing I’d ever put any effort into. Thanks go a world-wide pandemic1 I had a little extra time on my hands and figured I’d really give this a shot. Who knows, maybe I’d come out the other side of this pandemic with a new skill? Two years on and I can play several songs, carry a tune, and find it relaxing and enjoyable to play.

1. Focus + Practice + Time = New Skills

Part of my approach was to see if I could set aside some time every day to devote to learning. I thought back to a TEDx talk by Josh Kaufman entitled, “The first 20 hours — how to learn anything.” Josh outlines his process for learning the ukulele in 20 hours.

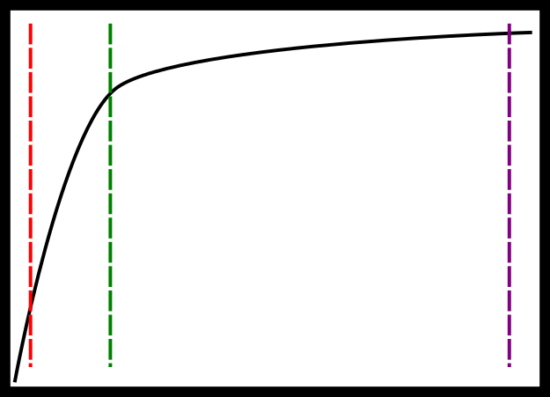

The essence of this talk is stuff we’ve heard a hundred times before. Small incremental improvements become big gains over time. Josh cites Malcom Gladwell’s theory that “ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness” as argued in his book “Outliers” but points out the 10,000 hours is to achieve world-class, expert-level greatness. Josh argues all you really need is twenty hours of focused deliberate practice to be pretty good at something. 2 This is amusingly similar to the Pareto Principle that “for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes.” This 20% of world-class effort, spread out over time, leads to surprising incremental improvements. 3 4 But, effort and time isn’t enough – it’s the particular focus. Fenyman’s learning technique is uniquely designed to help identify these features. A gross oversimplification of this method is: write down the steps as if you were explaining it to someone5 , identify gaps6 , organize / simplify and go back to the first step.

2. My Learning Process

What does all this rambling mean? This website tends to be my sketchbook / journal for projects – especially projects where I am starting from scratch. When learning a new topic or skill, my approach tends to be:

- Write down everything I know / have learned

- Identify gaps

- Break the skill into smaller chunks or modules

- Research chunks

- Memorialize what I’ve learned

- [Practice]

- Goto line 1

I used a similar process when it came time to build my first 3D printer, my first drawing robot, and vacuum former. My two year ukulele playing progress could be summarized as follows:

- Watched this ukulele tutorial series by “Andy Guitar,” probably dozens of times, while trying to follow along on my ukulele

- Found songs using the easiest beginner chords (Am, F, G, C)

- Retyped song lyrics, with the chords interspersed, in a way that made sense to me7

- Practiced those chords and songs

- Found more songs using additional chords (Dm, E7, Em, D, etc) and repeated steps 2-4

2. Building a DIY Travel Ukulele

But, this post isn’t about playing the ukulele. It’s about building a ukulele. Documenting all of this helps me organize my thoughts, get them out of my brain (since I know I can always return here to find them), and free up my attention to move onto new problems. (Perhaps most importantly, it lets me close dozens of browser tabs.) I’m not sure how I first stumbled across Daniel Hulbert’s YouTube videos and website, but ever since seeing some of his designs, I haven’t been able to shake the idea that I want to build my very own quiet little travel soprano ukulele.

If you’re following along so far, I’d warn you that as I’m writing this I just have a piece of wood with some holes in it and bits of hardware lying around. I would not consider what I have to be a tutorial at all. 8

1. Existing Tutorials, Resources, Examples

After looking at Daniel’s various designs, I also looked at several travel ukuleles (most inspired by Daniel’s work):

- David from Northamptonshire, UK built an interesting one with an amp “backpack”

- Soph from France made a cool “Avatar: The Last Airbender” themed uke

- Amy Qian of AmyMakesStuff.com documented her really gorgeous build and upgrades

- Anders Strand’s good looking, terrible sounding (his review, not mine) uke

- Demick’s build with a pre-assembled fretboard and custom build, including pickup

- Specific Love Creation’s video of his build

- Mike Hawkey’s build video

- JWillyGuy’s build video (his channel has a lot of great tutorials)

- Mike Gibbens’ build video

- Shaper Origin’s short travel ukulele build video

- TitchTheClown’s travel uke

- Stepanek’s build video (mostly a montage + music, but still)

I designed a 3D printable model, but have yet to print it. As I worked on the design, I deconstructed other designs I’d seen, looked at the important parts, including some from Daniel’s templates, and tried to keep the critical components and think about the various design choices he made in building his own instruments. However, I don’t think I ever will try to print this. From a learning perspective, it was an excellent exercise – but I think I’d much rather have a wooden travel uke.

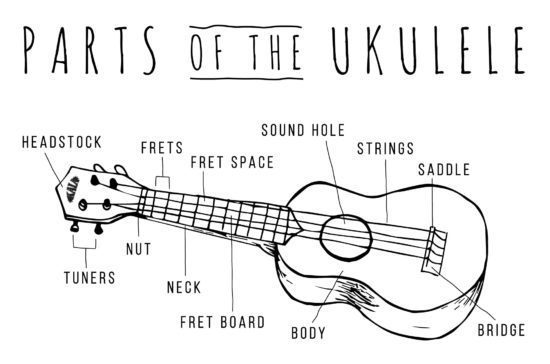

2. Anatomy Lesson

First, a bit of anatomy, swiped borrowed from the Kala website. (I wanted to leave a message letting them know I was borrowing the image, but the post doesn’t allow comments.)

3. Everything I Know So Far

The following list is a combination of several of Daniel’s blog posts, PDF downloads, and resources he cites. I will try to include the links to those references.

-

1. My Goals

- I want to make a soprano size acoustic ukulele with a shape similar to Daniel’s “travel [concert sized] ukulele (2015),” “backpacker travel [concert] ukulele (2015),” and “travel [concert] ukulele (2012)” but using the elements of his “basic hand tools.” The reason for the soprano size is because that’s the scale of my regular acoustic ukulele.

- The reason for wanting to use Daniel’s DIY hardware store components instead of fret wire for the frets is because I want to avoid the pitfalls described by Anders Strand in this blog post. If the slots for the fret wire aren’t cut to the same depth, well spaced, inserted to the same depth, and leveled properly, the instrument is likely to sound, to use Ander’s word, like “garbage.” 9 Daniel’s “hand tools” ukulele utilizes pieces of cotter pins super glued to the wood in place of this more exacting process.

-

2. (Re)Arrangement / Design Considerations

- Most of Daniel’s travel ukuleles use a “zero fret” instead of a “nut” to guide the strings on their way to the tuners. This lets him basically invert the strings, tying the strings above the zero fret where the nut would otherwise be, and place the tuners between the fretboard and the bridge.

- Chris Russell’s review of Daniel’s special custom travel ukulele had very few negatives and made a lot of interesting points. The head of the travel ukulele was tapered so as to allow it to be placed into a holder. Extending the head a little would allow it to feel more like a full sized ukulele. Recessing the strings into the head would allow them to be out of the way and less pokey.

-

3. Zero fret, frets, bridge

- The strings should have a slight incline from the nut (or zero fret) until it reaches the reach the bridge.

- Zero fret made from half of a 5/32″ cotter pin

- Remaining frets from half of 3/32″ cotter pins

- Bridge from a 3/16″ tube (aluminum, steel or styrene), about 3″ wide

-

4. Fretboard

- Of course, there’s no reason you couldn’t just buy a pre-made/slotted/measured fretboard and glue that down instead of messing with clipping cotter pins in half. These are widely available on Amazon, with fretboards, slotted fretboards, and pre-assembled fretboards available over at StewMac.com. If this scratch built ukulele doesn’t pan out, I might give that a try.

-

5. Strings

-

6. Tuners

- I’ve got these cheap ~$10 tuners on hand, but if this travel ukulele works out alright, I would definitely throw down for a set of the ~$30 Graph Tech tuners Daniel uses.

-

7. Super Glue

- I’ve always had horrible problems with super glue. It always dries completely up before I ever get a chance to use it. Fortunately, my twitter friends came to the rescue and recommended several brands:

- Mercury Adhesives M300M (suggested by @EMSL)

- Gorilla Glue (@MattStultz)

- Loctite (various)

- Bob Smith Industries (various)

- I haven’t tried it yet, but supposedly baking soda will help super glue cure faster

- I’ve always had horrible problems with super glue. It always dries completely up before I ever get a chance to use it. Fortunately, my twitter friends came to the rescue and recommended several brands:

-

8. Wood

- Anders recommends against using normal wood in favor of hardwood. While he doesn’t say why, I suspect it is because the strings were biting into the softer wood, causing the holes to widen slightly, and the ukulele to continually go slightly out of tune. He suggests the wood could be sourced from a cutting board, which seems like a pretty neat idea to me.

- Dimensions

- About +16 inches long (extrapolated from design)

- About 3 inches wide

- About 0.75 to 1.0 inch thick

-

9. Turn Around

- The turn around could be fashioned from an aluminum tattoo machine grip. Searching for “tattoo machine aluminum grip” on ebay seems to turn up some acceptable variations. The most good looking one appears to be about 2″ wide and a little over 3/4″ in diameter. Ebay links to particular auctions tend to go bad pretty quickly, so without any form of endorsement, I’ll link to the seller here too. (I’ve tried to save the auction page in Archive.org for future reference).

- However, since I have a 3D printer, these seem very printable. Anders was kind enough to post his 3D models for the parts of his ukulele. The design of the turn around is pretty simple. I published my own version on Printables.com. The model is little more than a 16mm diameter, 50mm long cylinder with a 5mm bore, some ridges for strings (spaced -17.75, -5.5, 5.5, and 17.75 from the center), and a flattened side to make it easier to print. These measurements came from Anders’ own work. I suspect the diameter, more, and ridge depths are immaterial, while the spacing is a little more important.

- The hardware for the turn arounds were a lot harder to track down. Daniel uses these super cool screws that go by an absolutely astonishing array of names. Chicago screws, Chicago bolts, sex screws, posts, binding posts, etc. Depending upon which one you search for, you’ll either find nothing, lumber, metal stakes, random screws/bolts, or something altogether very different. I’d found a truly dizzying array of options from McMaster-Carr, Home Depot, Lowe’s, Amazon, and a few other specialty sites. Fortunately, Daniel was kind enough to point me in the direction of these posts (with a #10-24 coarse thread size) and patiently explain he uses two of these with about 3/4″ of threaded rod between.

- There are some really nice looking black oxide posts on Amazon and elsewhere, but they tend to be metric, which then means drilling a metric hole, finding metric threaded rod… Because I like the look of the black oxide coated hardware, I was contemplating using some metric set screws in their place.

- I had considered using just one with a longer #10-24 machine screw10 on the other side – then I realized the screw side would be too narrow, creating a tilted turn around. Two posts it is. :) I don’t know the diameter of the post, otherwise I’d list that here. Another possibility is using post extensions.

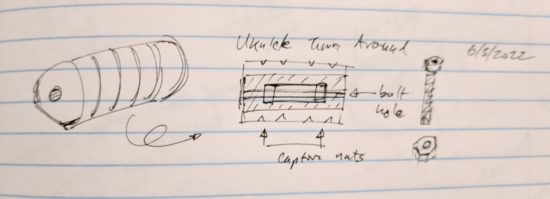

- Sometimes as I’m doing a deep dive on a project, I have an idea for an improvement or a way to do something in a different way from the original. It’s around this point imposter syndrome kicks in and I wonder “Is this actually a terrible idea that was already discarded by others?” I am sure the main point of having a post / threaded rod / post sandwich for the turn around is to ensure there’s a length of metal running through the turn around. It’s probably even more important if the turn around is made of plastic. Then again, what if there was a 3D printed turn around which had two spots for captive nuts and there was space on either side for two long machine screws / bolts? It would probably have most of the strength of a solid piece of metal running all the way through, far easier to source (and in black oxide hardware!), and fairly easy to assemble. Printing in plastic allows such cool options, such as embedded / captive nuts, why not leverage that ability here? A sketch:

Turn around sketch for 3D model, using captive nuts

-

10. Ordering

- I haven’t ordered all the parts, but it looks like the most likely route is for me to place an order with Home Depot and Amazon for the various parts. I’ll post links if/when I get the full shopping list together.

-

11. Tools

- Drill and drill bits for the tuners and turn around

- Hacksaw to cut out the rough shapes, possibly cut threaded rod if I was using that

- Coping saw to cut the interior area out nicely

- Nippers (left over from some tilework) to cut the cotter pins

- Files and sandpaper for taking the rough edges off the cotter pins and shaping the neck

-

12. Process

- Create template

- Transfer template

- Drill holes before cutting out the center, this way the wood in the center won’t splinter

- Cut rough shape of ukulele

- File, sand, and shape

- Glue cotter pins

- File, sand, and shape

- Add tuners, bridge, and turn around

I guess the next step is getting these ideas off paper11 and ordering some stuff!

Default Series Title- I guess that’s redundant [↩]

- He references his research for this figure, but doesn’t mention where it came from. Perhaps it’s in his book? I checked it out from the library, so I’ll let you know. [↩]

- I’m trying to find a good place to mention the Japanese word for the process of continuous improvement is “kaizen.” [↩]

- Another great distillation of these ideas is that 1% improvement every day for an entire year yields a 37.78 times improvement overall. [↩]

- Thus, these words! [↩]

- Thus, the open questions I’ll pose throughout [↩]

- I like this style [↩]

- A cautionary tale? [↩]

- If you choose to go that route, Daniel’s guides should be helpful. [↩]

- Machine screws being screws that don’t have a sharp tapered tip [↩]

- Or, the screen? [↩]