I recently stumbled across the world of fantastically charming mini prints and carved erasers by Serena Rios McRae aka Cactus Clouds Art. This short Instagram post provides an excellent overview of her process.

Serena’s artwork is evocative, accessible, and affordable. I bought several of her prints the other day. She also posts how-to’s on YouTube and provides plenty of links to her recommended supplies (Serena’s lists and affiliate links).

These looked like so much fun, I bought a pile of cheap pink erasers off Amazon, repurposed an old set of stamp carvers we had lying around (I had done some linoleum block printing back in high school and my wife had a small stamp making kit from years before), and gave it a shot. The kids had a great time with this while I fretted about whether they were going to jab their fingers and how many bandaids I’d have to have handy.

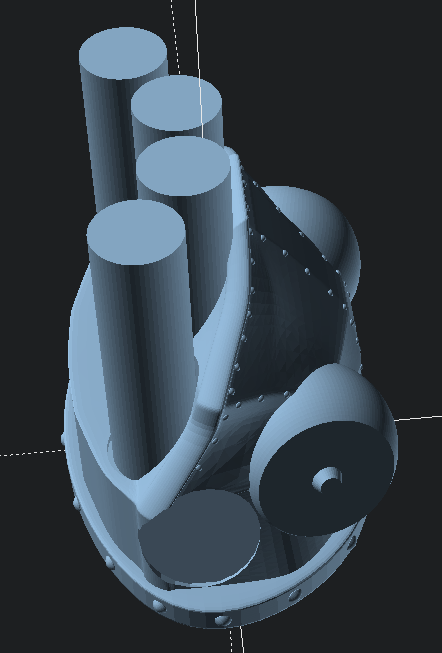

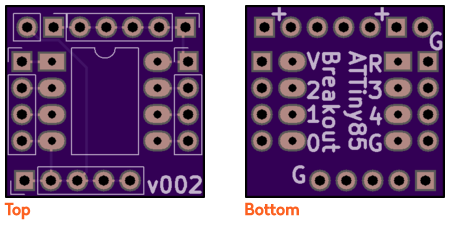

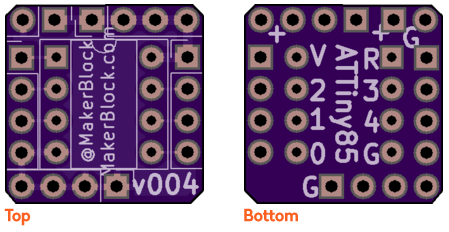

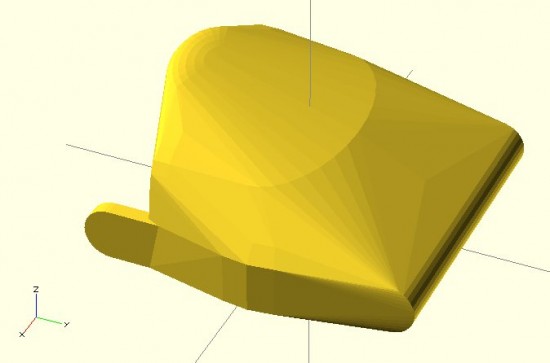

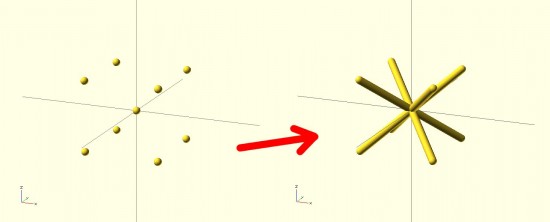

After their first stamp, I hacked together a 3D printed holder. Despite measuring the erasers carefully, it was too long and really, too big for what it needed to be. Here you can see version 01 taped to a piece of mahogany wood left over from my ukulele project.

There were several problems with this first attempt. The holder was a little too long, so the eraser would shift back and forth. It was also much bigger than necessary. I designed it with those large fins on the side to make it easy to tape down, but it really wasn’t necessary and just made rotating the eraser holder a little more unwieldy. While my kids were carving things using this holder, I went to work printing a few accessories.

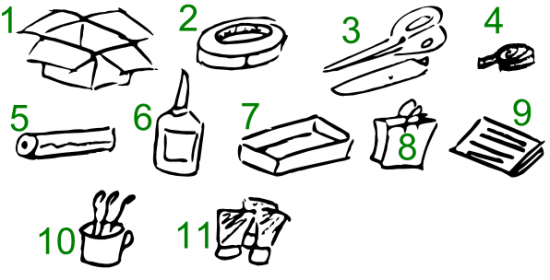

The blades came in a little plastic baggie, so I printed a bespoke screw top container for them so they can be stored securely. I also printed another blade handle so that two people could carve stamps at the same time – one using the original wooden holder and the other using the printed holder.

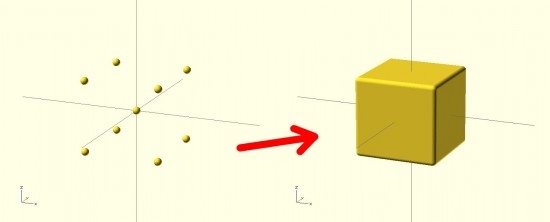

The next version was more compact and had dimples on the edges which I hoped would make it easier to hold. I also added some little ridges inside so the eraser wouldn’t fall through. Here they are:

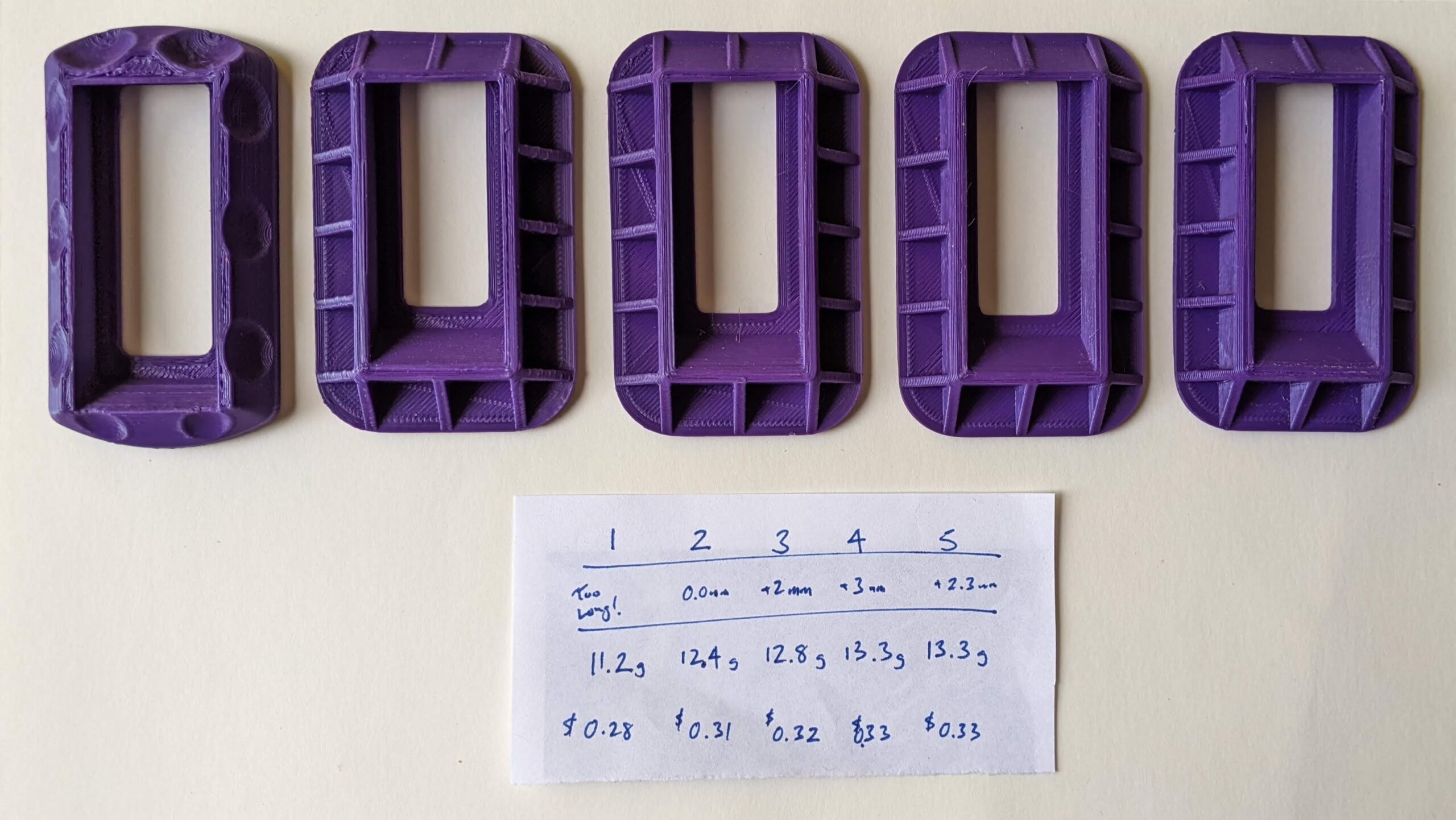

The dimples didn’t work. They weren’t deep enough and my hand couldn’t really grip it very well to keep it from moving while I was carving. The area for the eraser was a little too long. Versions 2-5 involved tuning the length just right. Each one takes about an hour to print and used about $0.30 of plastic. The final result fit the erasers like a glove. They nestle in the holder perfectly and are easy to poke out using the little hole. Admittedly, they might only fit the specific cheap erasers I found.

Here’s my process:

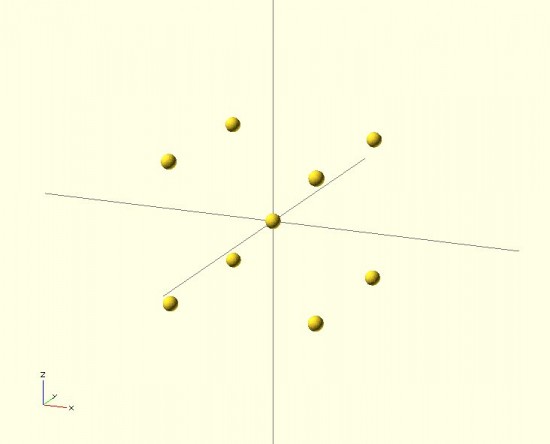

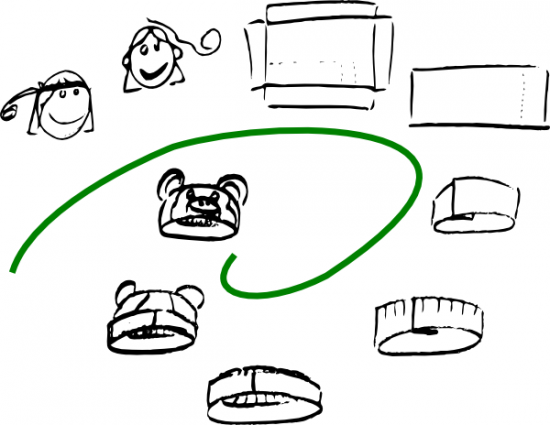

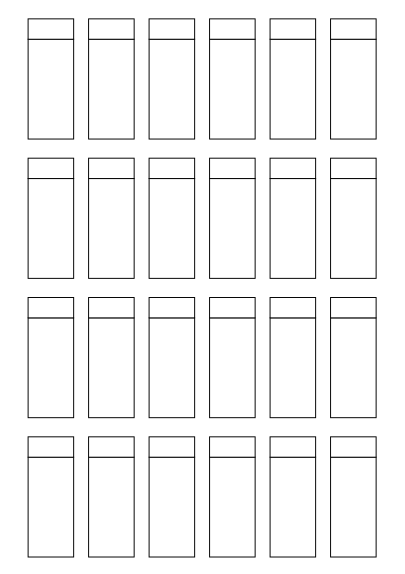

I created a page of eraser templates, which match the length and width of the large and small edges. Of course, the long section matches the long side of the eraser – but the shorter section only matches the short side of the eraser if you tip it over.

I got to use several iterations of the eraser holder for this next section:

The process is pretty easy. Put the eraser in the eraser holder – it should slip right in, drop in snugly, and lie flush with the top edge of the plastic holder. After cutting out a paper strip, it’s trimmed to size, creased to locate the central point, and a pencil drawing (drawn as I’d like to see it printed). This is taped upside down onto the eraser, rubbed along the back (a coin would work very well, but I just used one of the extra eraser holders), and the design is neatly transferred to the eraser. The neat thing about this process is that I could design something in Inkscape, print it into the template, and color it in with the pencil for transferring to the eraser.

Lastly, let’s see the result!

As you can see, the final stamped result matches the orientation of the little drawing. I just wish I’d saved the little scrap of paper with the original drawing on it! The eraser holder was a joy to use and the final result looks every bit as great as I was hoping.

If I keep making these, I’ll probably want to upgrade my setup to include Serena’s recommended stamp pad and sharpener (you’ll see them linked in Serena’s Amazon link above). I’d like to design something to make easy to hold the eraser, center it, and make a clean even stamp, but don’t have a great idea for one yet. I’ll keep pondering this and maybe whip something up this weekend.

Eraser Stamp Carving- I mean, I guess it’s version 1 – but I labeled all the purple ones starting with 1 so… [↩]