I’d like my computer to be smarter and more interactive and handle boring stuff for me and I’d also like to play around with some LLM / AI stuff… which brings me to this project. I’ve got a ton of basic things I’d love for it to do – manage lists, reminders, some Outlook functions, some media functions, and then also be able to interact with me – all via voice commands. Yes, you can do this with ChatGPT and probably others – but I am loathe to provide any outside resource with more of “me” (DNA, biometrics, voice, ambient noises, etc) than absolutely necessary. Plus, I’ve been tinkering with these little LLM’s for a while now and see just what I can build out of them and with their assistance.

I’m not great at Python1 , so I admittedly enlisted the help of some very large LLM’s. I started the main project in conjunction with ChatGPT, used Gemini to answer some basic questions about programming in Python syntax, etc, and Claude for random things. The reason for keeping my general questions in Gemini versus ChatGPT was so that I could not “pollute” the ChatGPT flow of discussions with irrelevant sidetracks. This was the same reason for separating out the Claude discussions too. I find Claude reasonably helpful for coding tasks, but the use limits are too restrictive.

My kiddo asked me how much of the code was written by these models versus my own code. I’d say the raw code was mostly written by LLM’s – but I’m able to tinker, debug, and… above all learn. I’d rather be the one writing the code from scratch, but I’m treating these LLM’s like water wings. I know I’m not keeping myself fully afloat – but I’m actually the one treading water, putting it all together, and learning how to do it myself. Also… said kiddo was interested in building one too – so I’m helping teach someone else manually, and learning more that way.2

Ingredients

As with many of projects, I started by testing the individual pieces to see if I could get things working. In order I started with validating individual pieces of the process:

- Could I get Python to record audio?

- Yep! Using import sounddevice, soundfile!

- Could I get Python to transcribe that audio?

- Could I get Python to use an API to run queries in LM Studio?

- Yep! Using the openai API, I could use python to send queries to LM Studio after an LLM had been loaded into memory

- Could I get Python to get my computer to respond to a “wakeword”?

- Yep! There’s another Python module for using “wakewords” using PocketSphinx. This was an interesting romp. I found that I had to really tinker with the data being sent to the Wakeword to be properly recognized and then fiddle with the timing to make sure what came after the wakeword was properly captured before being sent to the LLM. Otherwise, I ended up with “Jarvis, set a timer for 15 minutes” would become… “Jarvis, for 15 minutes” since the “Jarvis” would get picked up by the wakeword but the rest not caught in time to be processed by whisper.

- Can I get Python to verbally recite statements out loud?

- Yep! I used text to speech using Piper. However, this process took a while. One thing I learned was that you needed not just the voice model’s *.ONNX file, but the *.JSON file associated with it.

Until this point, I had wanted to try running LLM’s with the training wheels from LM Studio’s API. I really like the LM Studio program, but I don’t want to be dependent upon their service when I’m trying to roll my own LLM interface. Python can run LLM’s directly using “llama-cpp-python” – except that it will throw errors on the version of Python I was running (3.14) and was known to work with a prior version (3.11).

This lead me to learning about running “virtual environments” within Python so that I can keep both versions of Python on my computer, but basically run my code within a specific container tied to the version I need. Typing this command created the virtual environment within my project folder. The second command will “activate” that virtual environment.

- py -3.11 -m venv venv

- This created the virtual environment, locked to Python 3.11

- .venv\Scripts\activate

- This activates the virtual environment, so I can start working inside it

Back to work!

Building a Pipeline

This is where things really seemed to take off. I was able to disconnect my script from LM Studio and use Python to directly call the LLM’s I’ve downloaded. These were reasonably straightforward – and I was suddenly able to go from: Wakeword -> whisper transcribed LLM query -> LLM response -> Piper recited reply. Then, it was reasonably easy to have the script listen for certain words, and perform certain actions (setting timers was the first such instance).

Optimizations, Problems, Solutions

Building something that kind worked brought me to a new and interesting ideas, challenges, and problems:

- The original cobbled together process was something like: record audio, transcribe through Whisper, delete the recording, pass the transcribed statement to the LLM, give that statement to Piper, generate a new recording, play that recording. However, this process has some obvious “slop” where I’m making and deleting two temporary audio files. The solution was to find ways to feed the recording process directly into Whisper and feed Piper’s response directly to the speakers, cutting out the two audio files.

- I realized that I wanted the script to do more than just shove everything I have to say / ask into an LLM – to be really useful, the script would have to do more than just be a verbal interface for a basic LLM. This is where I started bolting on a few other things – like trying to call a very small LLM to try and parse the initial request to either:

- Something that can be easily accomplished by a Python script (such as setting a timer)

- Something that needed to be handled by a larger LLM (summarize, translate, explain)

- Something that maybe a small model could address easily (provide simple answer to a simple question)

- I ran into some problems at this point. I spent a lot of time trying to constrain a small LLM3 to figure out what the user wanted and assign labels/tasks accordingly. After a lot of fiddling, it turns out that an LLM is generally a “generative” model and it wants to “make” something. My trying to force it to make a choice among only a dozen “words”4 was really bumping into problems where it would have trouble choosing between two options, choose inconsistently, and sometimes just make up new keywords. Now, I could come up with a simple Python script which just did basic word-matching to sort the incoming phrases – but it seemed entirely counterproductive to build a Python word-matching process to help a tiny AI. I then tried building a small “decision tree” of multiple small LLM calls to properly sort between “easy Python script call” and “better call a bigger LLM to help understand what this guy is talking about” and quickly stopped. Again, my building a gigantic decision tree out of little LLM calls was proving to be a bigger task, adding latency and error with each call. I was hoping to use a small LLM to make the voice interaction with the computer simple and seamless and then pass bigger tasks to a larger LLM for handling, sprinkling in little verbal acknowledgements and pauses to help everything feel more natural. Instead I was spending too much time building ways to make a small LLM stupider, doing this repeatedly, and then still ending up with too much slop.

- And, frankly, it felt weird to try and lobotomize a small LLM into doing something as simple as “does the user’s request best fall into one of 12 categories?” Yes, small LLM’s can easily start to hallucinate, they can lose track of a conversation, make mistakes, etc. But, to constrain one so tightly that I’m telling it that it may only reply with one of 12 words feels… odd?

Over the last few days I’ve been tinkering with building an “intent classifier” or “intent encoder” to do the kind of automatic sorting I was trying to force an LLM to do. As I understand this process, you feed the classifier a bunch of example statements that have been pre-sorted into different “intent slugs.” The benefit of a classifier is that it can only reply with one of these “intent slugs” and will never produce anything else. It’s also way faster. Calling a small5 LLM with a sorting question could produce a sometimes reliable6 answer in about 0.2 ms, which is almost unnoticeable. Calling a classifier to sort should enable a 97% reliable result within 0.05 ms. This is so fast it is imperceptible.

I haven’t tried this yet. I’ve built up a pile of “examples” from largely synthetic data to feed into a classifier, produce an ONNX file7 , and try out. However, I wanted to pause at this juncture to write up what I’ve been working on. I say synthetic data because I didn’t hand write more than 3,000 examples on some 50 different intent slugs. I wrote a list of slugs, described what each one should be associated with, created a small set of examples, and then asked Gemini to produce reasonable sounding examples based on this information. 8 This list appeared pretty good – but needed to be manually edited and also tidied up. I wanted to remove most of the punctuation and adjust the ways numbers and statements showed up, because I’m simply not confident that Whisper will be able to accurately match “Add bananas to shopping list” to “Add bananas to ‘shopping list'” to something that the classifier will correctly interpret.

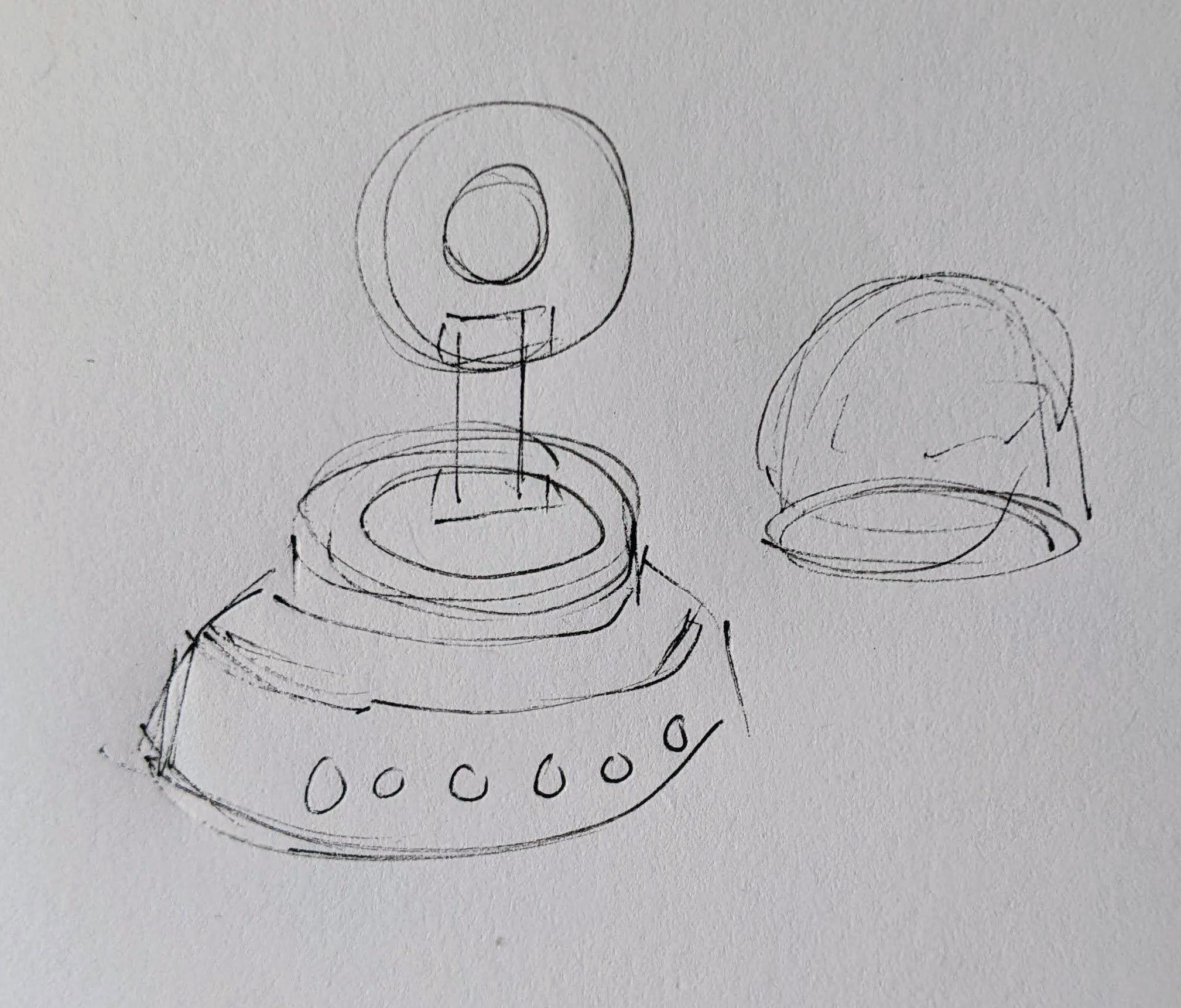

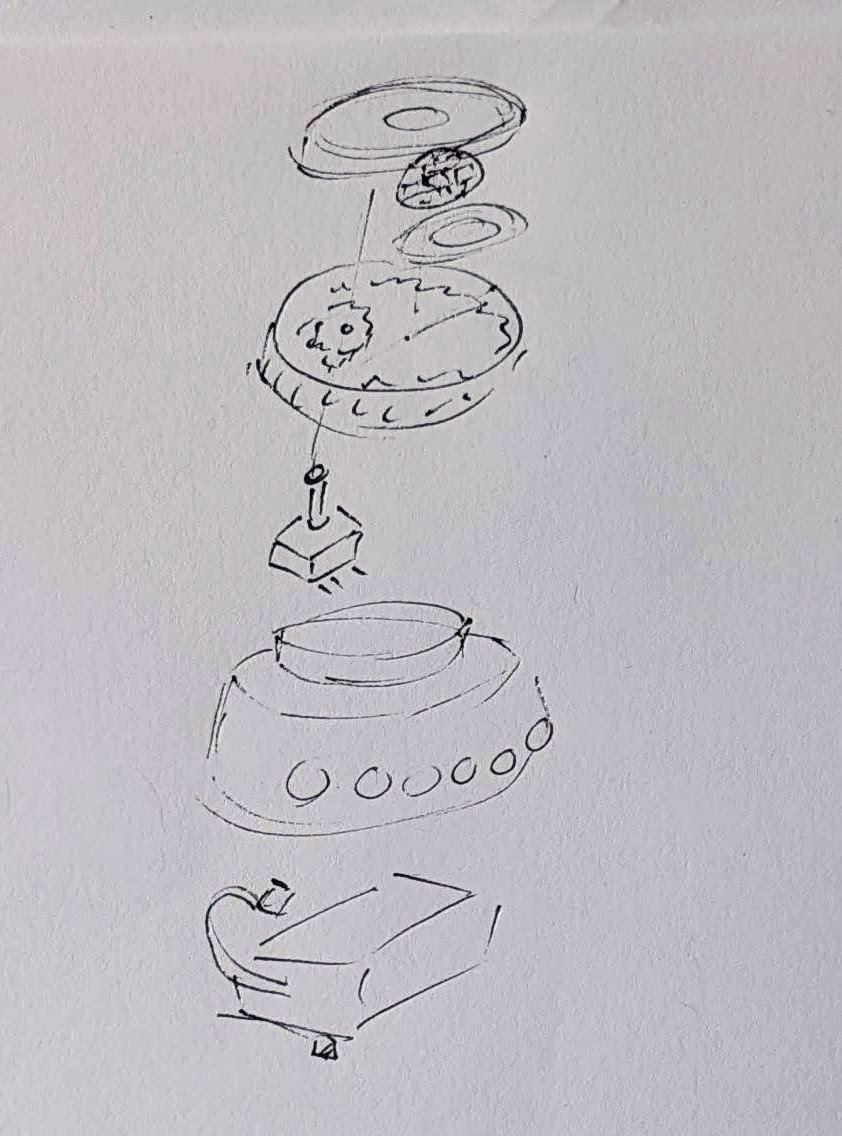

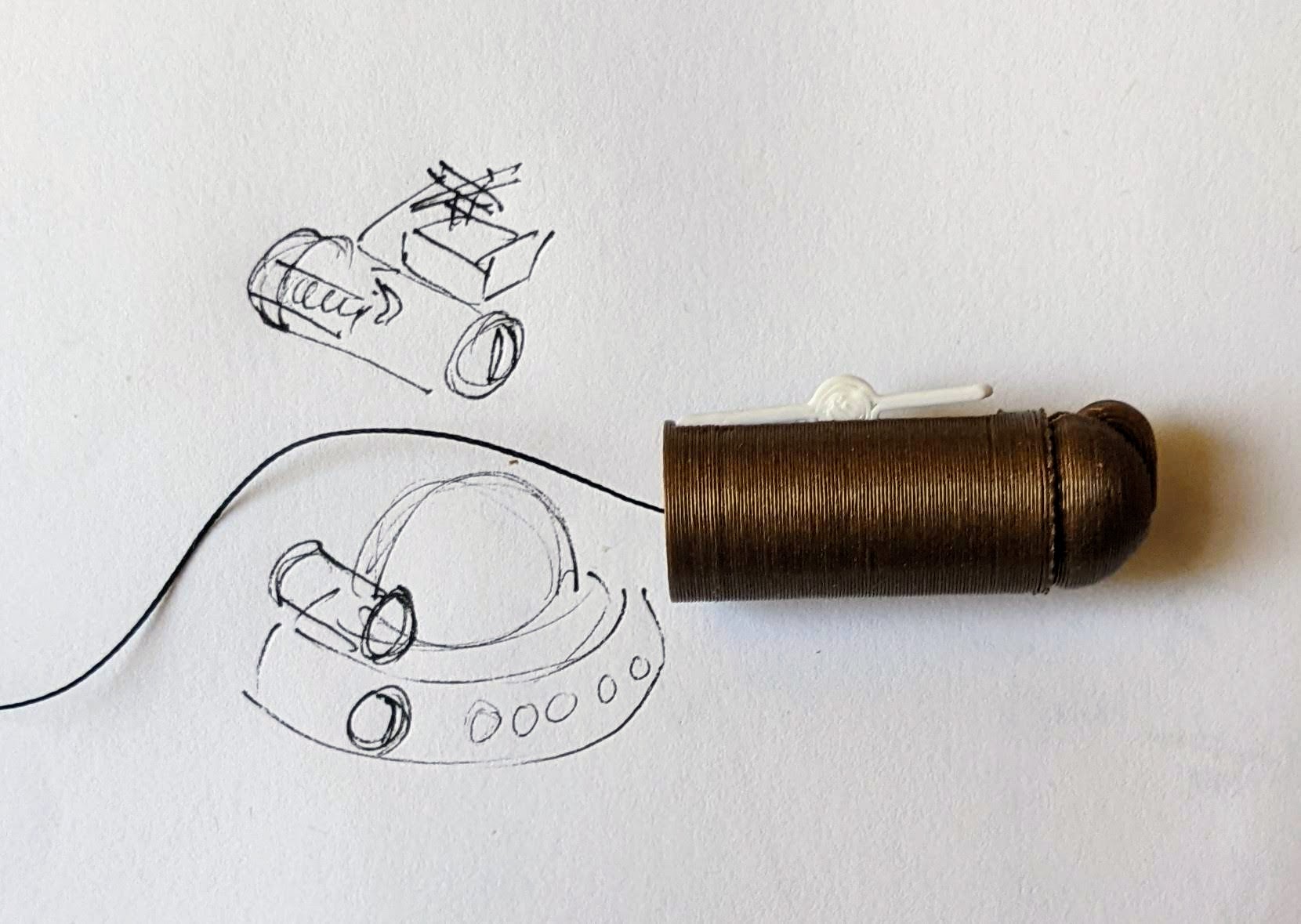

As I tinker with this project… I’m also looking at how I might be able to extend it into further projects. Not only might it be a great way to help me be more productive, but I might be able to create a really small version that could be put into a companion bot. A little companion bot with limited space, power, inputs, and abilities to emote could be far more lifelike, independent, and non-deterministic in it’s responses and actions.

Project Jarvis

- Yet!! [↩]

- Thanks Mr. Fenyman! [↩]

- Giving it limited context windows, limited tokens to use, highly restrictive system prompts [↩]

- Make timer, list timers, make a reminder, add to a list, recite a list, media buttons, etc [↩]

- ~1B parameter [↩]

- Let’s say 65% reliable [↩]

- Yes! Just like the voice models!! [↩]

- I know, more self-reflecting LLM garbage… [↩]