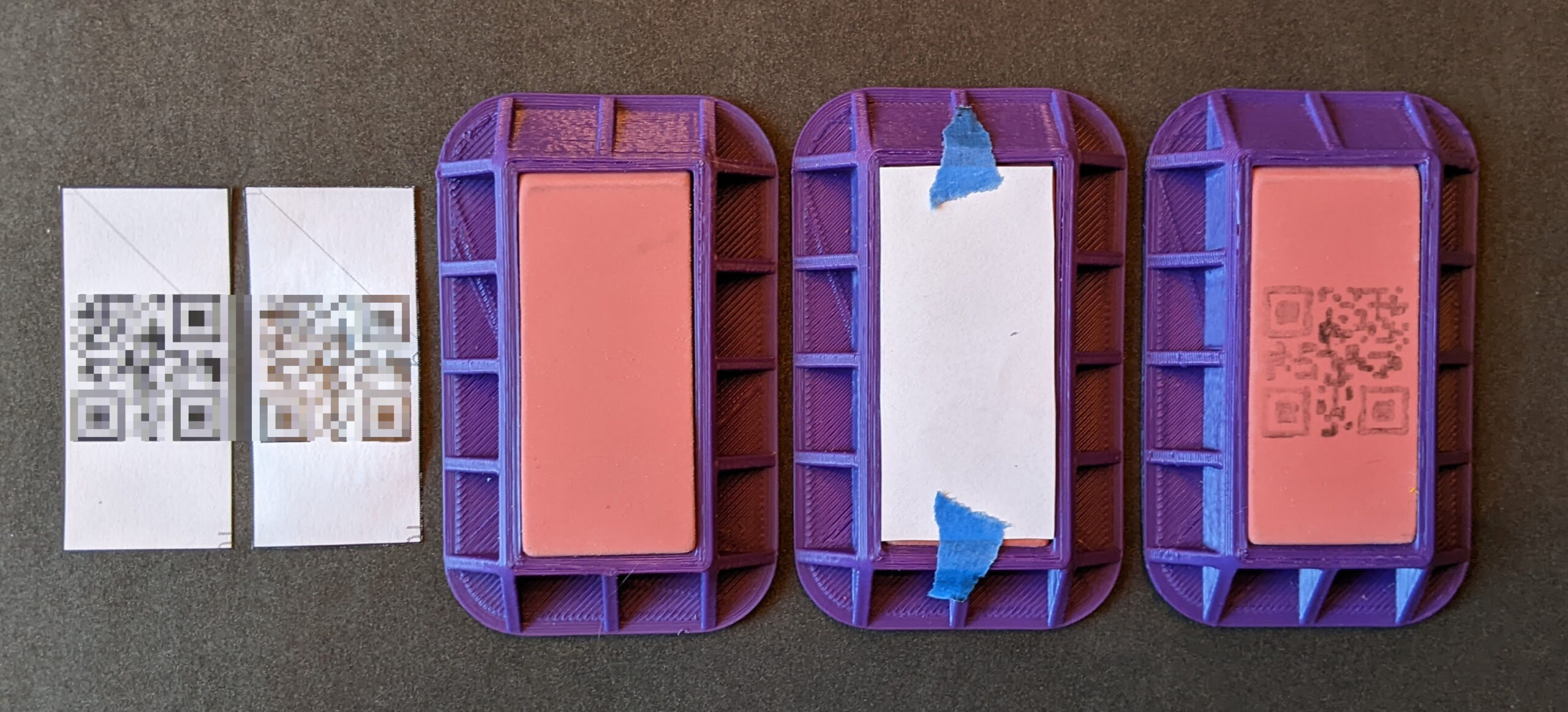

After some modest success carving some neat designs into pink erasers, I tried making a QR code stamp. It didn’t work well at all, with exactly just one impression working … sometimes.

The first attempt took a really long time and turned out terribly. After a few days break, and some mental distance from the project, I returned with some new ideas and inspiration.

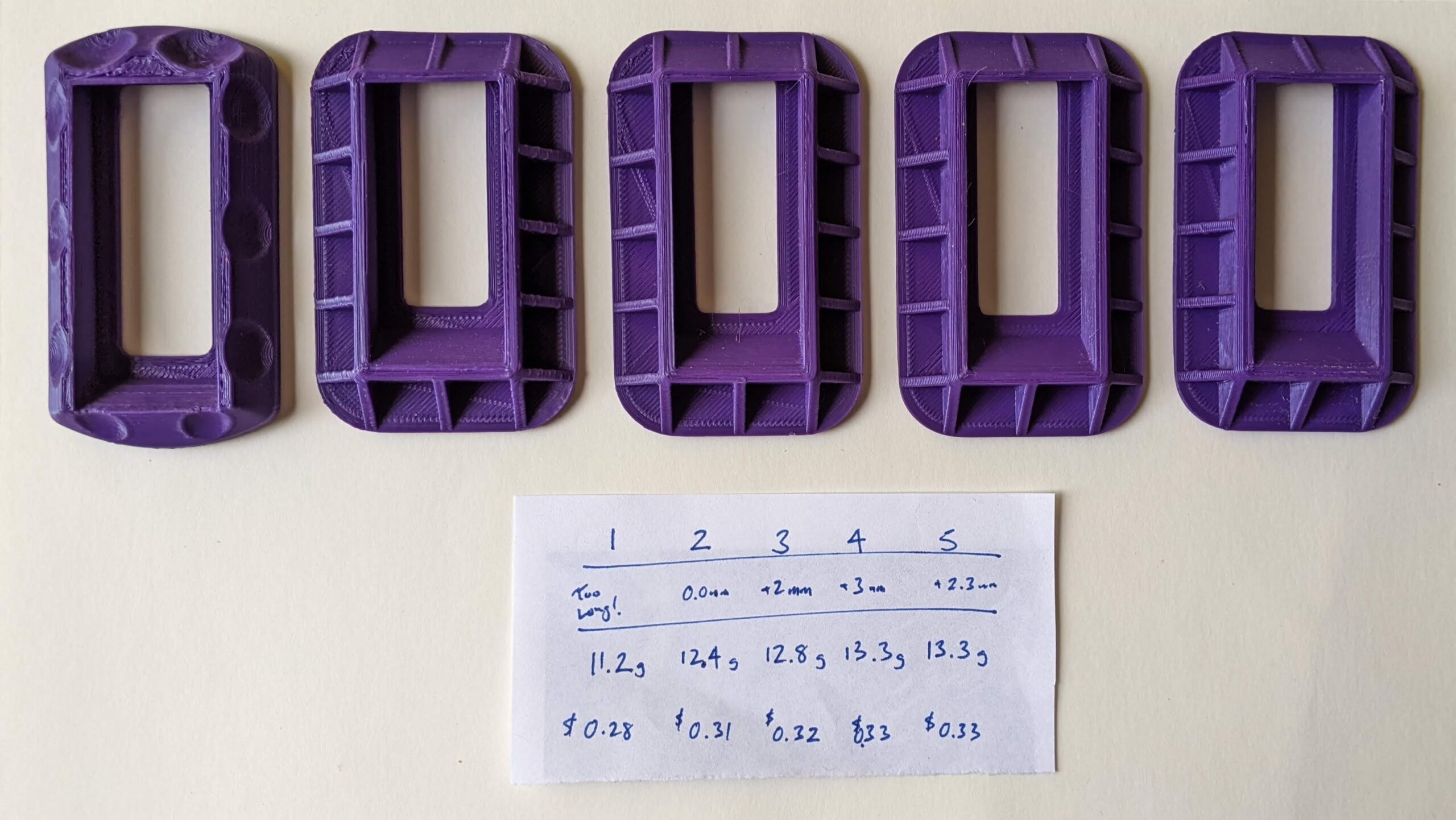

Here was my new approach and plan:

The Stamp

- Go Slow. Proceeding slowly and methodically is always a good idea with sharp instruments. I went fairly slowly the first time, but this time I would be even more methodical.

- Cutting. Rather than using the carving blades for the QR code features, I switched to using a craft knife. It was just too hard to cut precise lines with a V or U shaped blade, managing not just the direction and speed of the cut – but the depth as well – for both sides of the blade. The craft blade let me focus on just one side at a time. I used the blade to cut at about a 45 degree angle along one side, then other side.

- Don’t Cut Too Much. I used calipers to measure the pixels cut into my first attempt as well as the stamped result. I discovered \the stamp pixels were very slightly larger than their rubber counterparts. This tells me it would be better to cut too little rubber – and cut more later if necessary.

- Removing Scraps. Rather than sticking my big old fingers into the eraser or trying to pop it out with the blade, I used a pair of 3D printed tweezers to pluck them out.

The QR Code

- Optimize the QR Code. There are several ways to optimize a QR code for eraser / stamp carving. 1. I used as many of these methods as I could:

- “Pixel” Size.

- As you add more information into a QR code, the QR code generator will need to use more black and white units2 to encode the information. After some tinkering it seems like the smallest QR code that can be generated is 441 total pixels, 21 wide by 21 tall. The absolute largest QR code I could generate looks like one of those “magic eye” posters.

I didn’t even try to count how many pixels wide this thing was. It’s 9,216 pixels, 96 wide by 96 tall. - I was having a hard time carving a stamp 21 pixels wide into a 24.5 mm3 wide eraser, so the idea of carving more than 21 lines into an eraser by hand seemed not feasible. The very next step up from the 21×21 grid would be a 25×25 grid, so I knew I had to find a way to limit the data, find the best error correction, and find a way to cut these small pixels and thin features.

- As you add more information into a QR code, the QR code generator will need to use more black and white units2 to encode the information. After some tinkering it seems like the smallest QR code that can be generated is 441 total pixels, 21 wide by 21 tall. The absolute largest QR code I could generate looks like one of those “magic eye” posters.

- Proper Error Correction.

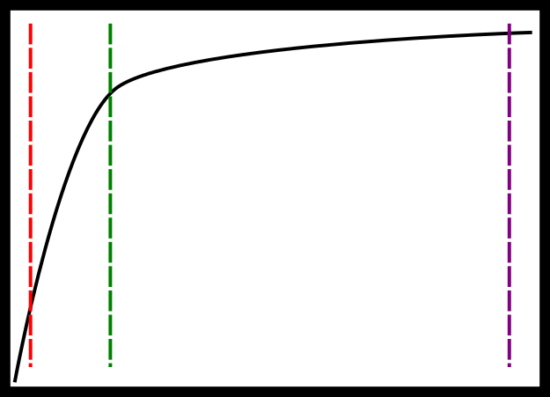

- QR Codes have built in “error correction” that allows the user’s scanning device to scan information from a partially formed, damaged, or obscured code. These settings range from L (low), M (medium), Q (quality), and H (high quality) able to error correct from up to 7%, 15%, 25%, and 30% damage respectively. Lowering the error correction allows you to create a smaller QR Code, but it will also be less robust.

- I fiddled with these settings a lot to find the maximum amount of data I could put into a QR code while still retaining a maximum size of 21×21 pixels. I was able to encode about 16 characters in a L, 13 characters in a M, 10 characters in a Q, 6 characters in a H. The code stores numeral easier and requires more pixels to store letters and special characters.

- My first attempt used an error correction level of L, but was basically unusable as there must have been more than 7% distortion. This time, I decided to try for a very high level of error correction with the Q setting for 25%.

- Reducing Data. This is where I used some tricks you may, or may not, be able to replicate.

- URL Shortener. A TinyURL link to my Instagram page requires 29 characters. Looking above, this would immediately suggest a 21×21 pixel QR code would not be possible.

- Trimming a Link. After some fiddling, I realized that as long as the data encoded looked like a URL (as in some characters separated by a “.”), the QR code scanner would interpret it as a link. This means we can skip the “http://” and “https://”, saving 7-8 characters! Unfortunately, this still doesn’t let me encode the shortest URL that TinyURL could give me which requires 20 characters after discarding the “http” stuff.

- Maybe Just a Domain? Maybe you just wanted to point someone to your website and not a big long link, shortened with a URL shortener. Let’s work the numbers backwards. Most commonly used domains end with “.com”, “.org”, “.biz” – with 4 characters each. Using the information above, this means we could use a domain name with up to 12 characters for an L encoded QR code, 9 for an M, 6 for a Q, and just 2 for an H. While it would be easy to find a 12 character domain, you’re stuck with only a 7% margin for your error correction. A domain with 6 to 9 characters for Q and M would allow for 25% and 15% error correction. You can still find 6 character “.com” domain, but… they’re unlikely to be very memorable. This isn’t necessarily a problem. You might be able to find a good short domain with an unmemorable name, but forwards the user to your real website. The problem, of course, is that no one is going to want to click on that link.

- How About a custom URL Shortener? It’s still possible to purchase a short URL, but they’re pricey. I happened to buy a good one several years ago and have hung on tightly to it. I slapped a YOURLS install on it, and have been using it ever since. Using my own URL shortener means I can keep the URL down to just 9 characters – including the TLD!

- “Pixel” Size.

Okay, back to carving. I grabbed my headphones, put on some music, and took it very slowly – a little under two hours. Here’s some progress photos:

Here’s how it looked (with some additional shots to show the original design overlaid):

I stamped this design 9 times – and all 9 were more or less easily scannable. The neat thing about this design is that it points to a URL shortener I own, so not only is it about as tiny as possible, but I can change the destination if I ever needed – without having to spend two hours recarving an eraser stamp!

Eraser Stamp Carving- I won’t get too much into the weeds on the actual method of generating QR codes, mostly because I haven’t studied the math in it, but I did find a great article which has a lot of good background info and explanations [↩]

- I’ll call them “pixels” from this point forward [↩]

- Just barely under an inch [↩]