Much like those recipes on the internet where the author tells you their life story or inspiration, I’ve got a lot to share before I get to the punchline of this blog post (a bunch of CircuitPython tweaks). Edit: On second thought:

- Keep the lines of code <250

- Try using mpy-cross.exe to compress the *.py to a *.mpy file

This is a bit of a winding road, so buckle up.

Admission time – I bought a Prusa1 about three years ago, but never powered it on until about a month ago. It was just classic analysis paralysis / procrastineering. I wanted to set up the Prusa Lack enclosure – but most of the parts couldn’t be printed on my MonoPrice Mini Delta, which meant I had to set up the Prusa first and find a place to set it up. But, I also wanted to install the Pi Zero W upgrade so I could connect to it wirelessly – but there was a Pi shortage and it was hard to find the little headers too. Plus, that also meant printing a new plate to go over where the Pi Zero was installed, a plate that I could only print on the Prusa, but I didn’t have a place to set it up…

ANYHOW, we’ve since moved, I set up the Prusa (without the Pi Zero installed yet), printed a Prusa Lack stack connector to house/organize my printers. Unlike the official version, I didn’t have to drill any pilot holes or screw anything into the legs of the Lack tables.

Once the Lack tables were put together, I set about putting in some addressable LEDs off Amazon. I found a strip that had the voltage (5V for USB power), density (60 LED’s per meter), and the length (5 meters) I wanted at a pretty good price <$14, shipped. I did find one LED with a badly soldered SMD component which caused a problem, but I cut the strip to either side of the it, then soldered it back together. Faster and less wasteful than a return at the cost of a single pixel and bit of solder.

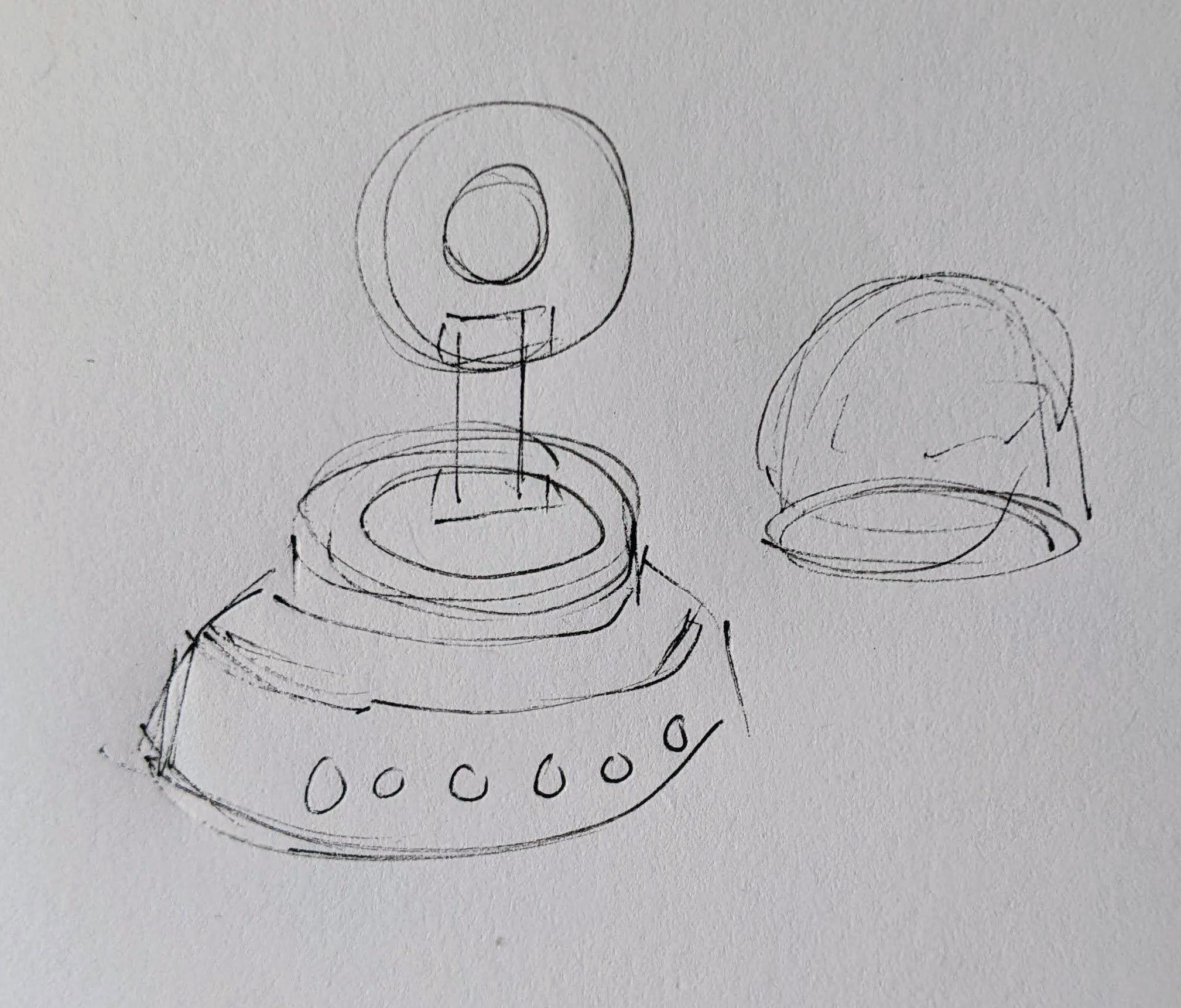

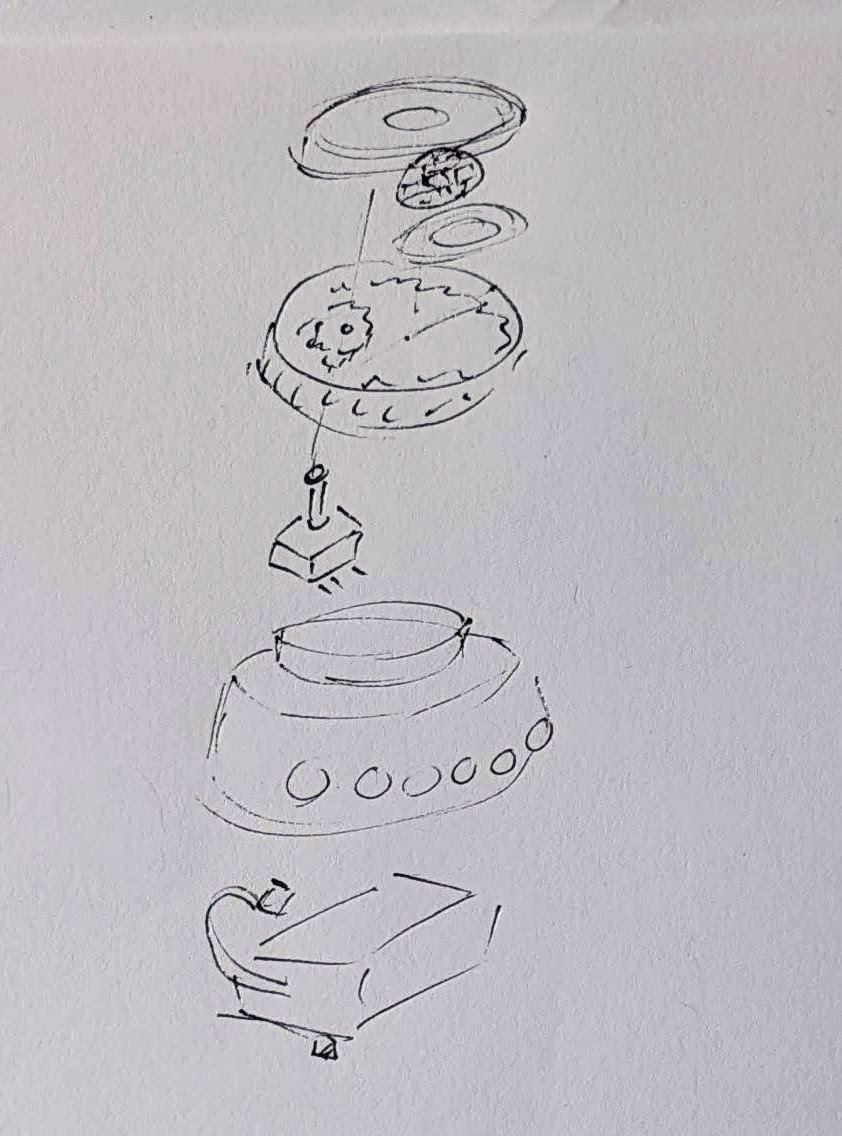

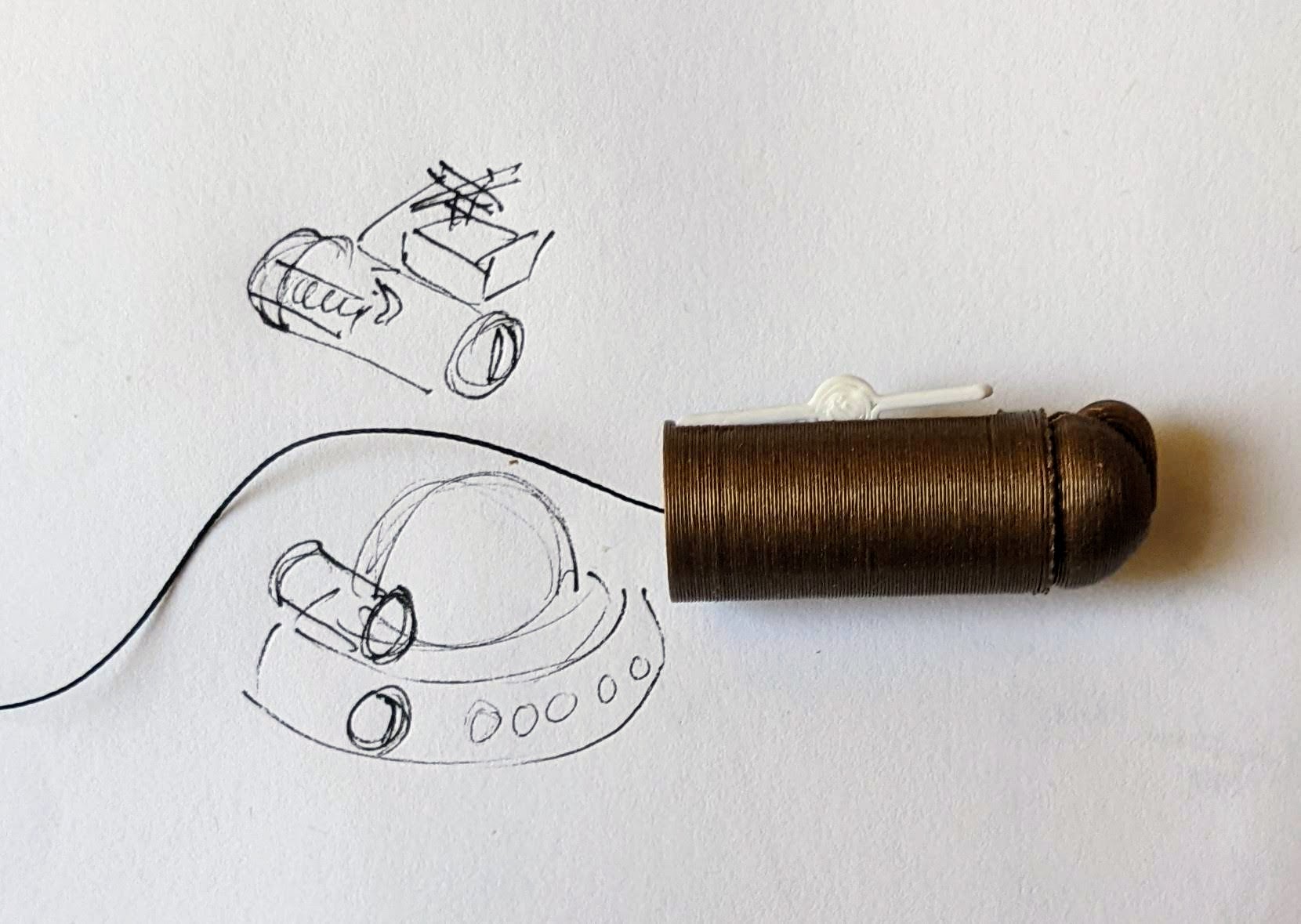

The Lack stack is three tables tall, keeps extra filament under the bottom of the first table, my trusty Brother laser printer on top of the first table, my trusty Monoprice Mini Delta (Roberto) on top of the second table, and the Prusa (as yet unnamed Futurama robot reference… Crushinator?) on top. Since I don’t need to illuminate the laser printer, I didn’t run any LED’s above it. I did run a bunch of LED’s around the bottom of the third printer… this is difficult to explain, so I should just show a picture.

When Adafruit launched their QtPy board about four years ago, I picked up several of them. I found CircuitPython was a million times easier for me to code than Adafruit, not least of which because it meant I didn’t have to compile, upload, then run – I could just hit “save” in Mu and see whether the code worked. I also started buying their 2MB flash chips solder onto the backs of the QtPy’s to a ton of extra space. Whenever I put a QtPy into a project, I would just buy another one (or two) to replace them. There’s one in my Cloud-E robot and my wife’s octopus robot. Now, there’s one powering the LED’s in my Lack Stack too.

I soldered headers and the 2MB chip into one of the QtPy’s, which now basically lives in a breadboard so I can experiment with it before I commit those changes to a final project. After I got some decent code to animate the 300 or so pixels, I soldered an LED connector directly into a brand new QtPy and uploaded the code – and it worked!

Or, so I thought. The code ran – which is good. But, it ran slowly, really slowly – which was bad. The extra flash memory shouldn’t have impacted the little MCU’s processor or the onboard RAM – just given it more space to store files. The only other difference I could think of was that the QtPy + SOIC chip required a different bootloader from the stock QtPy bootloader to recognize the chip. I tried flashing the alternate “Haxpress” bootloader to the new QtPy, but that didn’t help either. Having exhausted my limited abilities, I turned to the Adafruit discord.

I’ll save you from my blind thrashing about and cut to the chase:

- Two very kind people, Neradoc and anecdata, figured out the reason the unmodified QtPy was running slower was because the QtPy + 2MB chip running Haxpress “puts the CIRCUITPY drive onto the flash chip, freeing a lot of space in the internal flash to put more things.”

- This bit of code shows how to test how quickly the QtPy was able to update the LED strip.

- from supervisor import ticks_ms

- t0 = ticks_ms()

- pixels.fill(0xFF0000)

- t1 = ticks_ms()

- print(t1 – t0, “ms”)

- It turns out the stock QtPy needed 192ms to update 300 LED’s. This doesn’t seem like a lot, until you realize that’s 1/5th of a second, or 5 frames a second. For animation to appear fluid, you need at least 24 frames per second. If you watched a cartoon at 5 frames per second, it would look incredibly choppy.

- The Haxpress QtPy with the 2MB chip could update 300 LED’s at just 2ms or 500 frames per second. This was more than enough for an incredibly fluid looking animation.

- Solution 1: Just solder in my last 2MB chip. Adafruit has been out of these chips for several months now. My guess is they’re going to come out with a new version of the QtPy which has a lot more space on board.

- Even so, I’ve got several QtPy’s and they could all use the speed/space boost. I’m not great at reading/interpreting a component’s data sheet, but using the one on Adafruit, it looks like these on Digikey would be a good match.

- This bit of code shows how to test how quickly the QtPy was able to update the LED strip.

- The second item was a kept running into a “memory allocation” error while writing animations for these LED’s. This seemed pretty strange since just adding a single very innocuous line of code could send the QtPy into “memory allocation” errors.

- Then I remembered that there’s a limit of about 250 lines of code. Just removing vestigial code and removing some comments helped tremendously.

- The next thing that I could do would be to compress some of the animations from python (*.py) code into *.mpy files which use less memory. I found a copy of the necessary compression/compiler program on my computer (mpy-cross.exe), but it appeared to be out of date. I didn’t save the location where I found the file, so I had to search for it all over again. Only after giving up and moving on to search for “how many lines of code for circuitpython on a microcontroller” did I find the location again by accident.. Adafruit, of course. :)

- I’m pretty confident I will need to find the link to the latest mpy-cross.exe again in the future. On that day, when I google for a solution I’ve already solved, I hope this post is the first result. :)

The animations for the Lack table are coming along. I’ve got a nice “pulse” going, a rainbow pattern, color chases, color wipes, and a “matrix rain” / sparkle effect that mostly works.

I started this blog post roughly 7 months ago2 by the time I finally hit publish. After all that fuss, ended up switching from CircuitPython (which I find easy to read, write, maintain, update) to Arduino because it was able to hold more code and run more animations. Besides the pulse animations, rainbow patterns, color chases, color wipes, and a matrix rain, it’s also got this halo animation, some Nyan cat inspired chases, and plays the animations at a lower brightness for 12 hours a day (which is intended to be less harsh at night). I could probably add a light sensor, but I don’t really want to take everything apart to add one component.