I like to think about projects in discrete parts, trying to solve one part, then moving onto another section. In the case of this DIY lightsaber build, I’ve been burning some brain cells thinking about this project. Just by looking at the publicly available images of the TwistSaber, what can I infer about it’s construction?

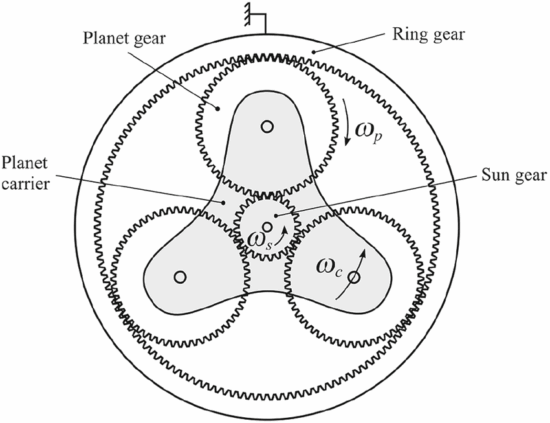

Planetary Gears

I would guesstimate the gears are probably about 8 mm in height. When I want to make a very sturdy part, I’ll use a 3 mm thickness. However, these gears look extra chonky, so let’s go crazy. Making further, and more in depth, guesses… Let’s see what happens when we toss the above image into Inkscape and try to lay some star shaped polygons on it.

I would estimate the ring gear has 58 teeth, the planetary gears appear to have 20 teeth, and the sun gear to have 10 teeth. When you’re dealing with printing with tight tolerances and thick (0.4 mm) extrusions, you can’t make the teeth too small, but you need enough teeth so permit smooth operation. In any case, we can count on some sweet OpenSCAD gear library magic to help us design these planetary gears.

Screw Threads

Since we’re already talking about the planetary gears, let’s think about the spiral core rotations and screw thread. If the 58 tooth ring gear goes through a half rotation, it will rotate the 20 tooth planetary gears by 26 teeth, causing just over 2 rotations of the 10 tooth central sun gear. The math should math like this:

- ((ringTeeth / planetaryTeeth)) * (0.5 rotations) * (planetaryTeeth / sunTeeth) =

- (58 / 20) * 0.5 * (20 / 10) =

- (58 /

20) * 0.5 * (20/ 10) = - 58 * 0.5 / 10 =

- 29 / 10 = 2.9

This tells us the half turn of the hilt should cause nearly 3 turns of the central spiral core. If we had a zero degree spiral around the central core, the screw thread would not be a spiral but rather a straight vertical line. If we had an absolutely crazy spiral, like a million degrees of turn, the screw thread would be nearly horizontal. We’re going to need a slope for the screw thread that causes 2.9 revolutions over 200 mm.

Screw Core

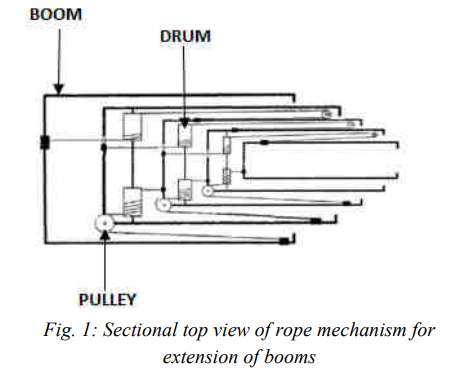

The three central screw segments have some interesting design elements.

By tracing the image of the screw threads, in alternating yellow and red, we can see the path of the screw threads on the camera facing side of the tube. However, by duplicating these tracing and flipping them along a horizontal axis, we can see this means there’s just two screw threads. In an earlier post I had wondered at the optimal number of screw threads. You want sufficient separate threads to work to actuate the core evenly, but not so many that they introduce unnecessary friction.

We already know from various videos and GIFs the screw core is attached to the hilt at the thinnest of the three segments. It’s interesting then that the two larger tubes have flared ends with rounded notches on one side. Although I don’t have a photo or still frame to show this, I suspect these are meant to lock against the base of the blades. My working theory is you insert the core into the nested blade segments, and then pull them back so they click into the base of the blades.

Here’s my thinking… let’s assume the spiral core pieces do not connect to the blades segments at all – except at the very bottom and very top. When you rotate the spiral core center, the other two core segments could extend – but might do so unevenly based upon how much friction there might be between any two adjacent parts. If the spiral core pieces do connect to the blade segments, then each of the three blade segments should actuate at the same rate (rather than whichever one has the least friction).

I need to give this more thought – I have an idea, which if correct might be a simpler way to design this mechanism for 3D printing. (It would be probably impossible for injection molding though…

Blade Segments

The blade segments are interesting in their own right. There’s no clear picture of how many rails exist within these blade parts. However, we might be able to extrapolate this from the portions we can see. In the second of these two screen shots, you can see two and a half sets of rail alignment nubs. If there is an equal number on the reverse, then perhaps there are five alignment rails inside each blade?

One nice thing about OpenSCAD is the use of parameters. There’s no reason I couldn’t design a similar device, but specify the blade segments should only be 20 mm tall, and then print out an incredibly stubby light saber. If the mechanism work, then I could just adjust the blade segment height from 20 mm to 250 mm and try printing it again.

DIY Lightsaber Build

There is probably a sweet spot between enough threads to keep the blade in aligned, but not so many that the extra friction causes the blade to bind.

There is probably a sweet spot between enough threads to keep the blade in aligned, but not so many that the extra friction causes the blade to bind.